Select Work

Flyway Journal of Writing & Environment. Winter/Spring 2024. “The Extinctionglass.” Short story.

Minerva Rising. Issue 23: Subversion. 2024. “Self-Portrait as Sirens,” “Wake,” “Lethe,” “Wasp Woman.”

Haiku Expo. Arizona Matsuri: A Festival of Japan. 2024. “Saguaro in Bloom.” Honorable Mention in Adult Category.

Waxing. Issue XXIX. Fall 2023. “Bonneville,” “Pando Aspen Clone,” “Metamorphosis of the Pale Tussock on a Plum Tree Branch.”

High Country News. July Issue. 2023. “Sister Storms.”

Look Again Series with artist Julie Lapping Rivera. 2022. Jovita Idár: “Inviting the Broad Horizons.”

Digging Through the Fat. 2021. “Walking with You in Santorini”

Artivisim4Earth at U of Utah. 2021. “Fire-Activated.” For full collaborative project, click here.

Blackbird. 2019. “Canción de Cuna” and “Zero, 2018.”

New Ohio Review. 2019. “Now In Color.”

Anomaly. 2018. “The Other Side of Giving” and “My Life.”

Canary: A Literary Journal of the Environmental Crisis. 2017. “Without the Flood.”

Interim: A Journal of Poetry and Poetics. 2017. “oscuro,” “rueda,” and “huerta.”

Wildness Journal. Platypus Press. 2017. “Scene 1: Doorway,” and “Scene 2: Everyone had expectations about what should happen next.”

Blackbird. 2016. “Accountability for Your Blind Sheep,” “Somewhere Else in Texas.”

Connotation Press. 2016. “This Name,” “Azul for Water,” and “The Dead Dream Us.”

Qu Literary Magazine. 2016. “Water Theory.” and “Hero,”

Cider Press Review. 2015. “Melanie Griffith and The Lion.”

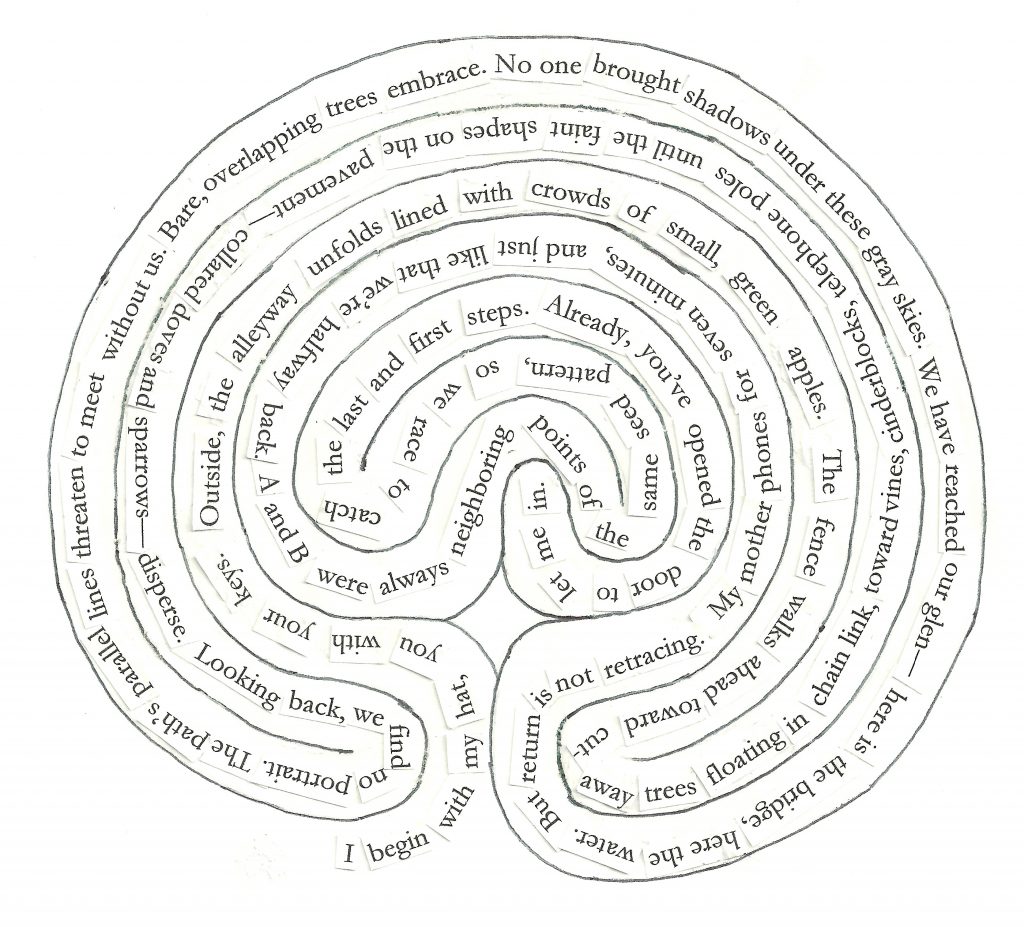

previously published in Halophyte Magazine: Mapping/Walking

Giants’ Faces Held in the Hills

Late morning we occupy the space of our shadows

escorted each week through the yard of small white stones,

of whale-blue buildings named Palo Verde, Cactus, Kennedy,

Roosevelt, and the two spruce trees called sentries.

Neither inmate nor correctional officer,

I am between their words and the invisible women

that occupy workshop with descriptions of their hair

like water from a dry spring. My co-instructor and I,

we are new statues. We are pinstriped cotton shirts

and blue pants. We are slender fish between the gates. We

are our family’s names beside students also fathers, also

husbands, also sons, also inmates in their orange reminders.

Here they say, we are not cyclopses. Thank you for not staring.

We talk about Bishop’s fish returning to the water

with its hooked gums, about Pound’s apparitions.

It seems this prison is also a world beneath worlds.

Its residents speak to the outside from booths beneath sentries.

On ceremony, some gather in the sweat lodge gated under sun.

And I see none of this until a morning when the yard

is clear of orange, when we look past our shadows and theirs.

At its finish, they say, drive safe. We exit the yard.

Exit sally port, returning our radios. Exit door and outer gate until

the desert is un-netted from barbs and chain link. Until next time,

we return to giants’ faces held in profile against the dark hills.

previously published in cream city review

Lion Lights

—after Richard Turere’s invention to protect livestock near the Kenyan savanna

We may never know what it’s like for a predator to enter our gate

and drag away the cow / We may never know / what it is like to be the predator

found in the grass / then dragged into town by the hind paws

hearing this is my territory / That is yours

Cows didn’t always live by the savanna / neither did the boy

who leads them to grasslands / who says / A lion for a cow

What does it matter / after both lie still in the yard / the lions

still coming / The boy builds the compromise

in a modified car battery / linked to lights running off solar

after so many shunned scarecrows / hung

dewy and limp / At night / torch bulbs flash for the lions

glinting off their eyes / glinting off the dull cows’ eyes

So the lions move toward zebra foals / The boy

enters in the morning with feed and draws the milk / We want to say

to ourselves Lion is a thief / is a drunk driving their car

into our tree / is a mortician / who steals corneas / But no

The lion / is a lion / was / will be a lion / We don’t know

what a lion is outside / the cage / the channel / the big cat rescue farm

How are we / outside the lion / Sometimes we’re just

straw stuffed in our old clothes / sometimes we move / Lion moves too

previously published in The Citron Review

The River

The river arrives from high heels, crossed legs, pregnancy.

Who knows? It’s dappling her thigh now in purple,

green reeds, and yellow mushrooms.

Bog turtle, salamander, pink river dolphin

gathered here in jars, exist in her along shallows

shaded by overgrown trees, the narrow hulls of boats nesting.

Some say my mother’s veins are drowned water

from the Ice Age, when the original stream was flooded over.

And if that’s true, her veins are less a map and more

a pattern of lightning strikes.

Once we were all in the estuary of her.

Once we were axolotl pressing our newfound hands

into the river bottom, pushing off.

previously published in New Plains Review

Tour of the Golden Gate: An Epilogue for Kees

Mom’s harbor cruise has us

pinched by the cold edges of sky

and its momentary shadow. We rock, catching ourselves

while the bridge overhead promises to stay

and the wind rasps, curling hair into knots.

We snap pictures of the latticed triangles

pointing heads, pulling the bridge into one,

and I can’t help thinking of death,

the hole we all orbit toward.

Brief as a plunge breaking and burying

that exclamation of flight.

Later, on its paved arch and knobby bolts,

we admire the red tubes, riding from dock to tower.

And everyone waits a moment, to count the rails and suspenders,

to lean over the side, to watch people looking back.

It’s the human condition to be in transit—

always east of setting desires on the missed bus,

on the twinkling plane ascending into the dark.

When I think of you alone on the pier

or stepping on a cigarette outside Bimbo’s 365 Club,

I see that it’s easier to follow in groups, to refuse the homeless,

and to watch our step when they say so.

But sometimes we take comfort in thinking we might be missed

if our minds were in such a state to leap, to get away.

I try to believe they are the same thing—death

and that long walk to Mexico.

previously published in Solo Novo: Art and Revolution

esperanza [ES-pear-AHN-sah] noun (f) :

Migration is written on this green heartache

of home, once its own discovery of water—

the Aztecs’ Metztlixcictlico meaning

place in the center of the moon.

Some are used to hopes being what they’ve been.

But singing one octave is Kansas to Oz. For a while,

my father didn’t know that the movie changed

to Technicolor since the family TV was black and white.

salvaje [sahl-VAH-heh] adjective :

In grief, we cannot explain the body’s

tenderness, its heaviness.

Without tears, the animal nurses

an old shoe for weeks.

previously published online in Public Pool: One Space for All Poets (website discontinued)

You and I Saw the Animals

1.

Lion summertime swallowed us up year after year.

We sisters picked neighbors’ apricots, peaches, nectarines.

We swung our legs—acrobats on ponies—from bike pedals to handlebars.

We puffed air into the nylon of our swimsuits

to make breasts like mermaids, the water holding them up.

That was when we started wearing swimsuits.

We were wetting our hair in front of our faces

then rolling the damp sheet of it back

to look like George Washingtons,

the hose twirling in the pool

until the last warm day had already passed,

the water too cold for you and for me.

2.

We listened to longer books on our parents’ bed,

illustrated Greek mythology. How silly all those gods and grown-ups,

chasing the sun, opening boxes, looking back.

Odysseus had built that olive tree bed, each bedpost

a growing tree trunk. But Penelope was alone, sleeping

on the left or right side of the bed, then spread out in the middle.

Each night, it was as if we could undo our own weaving . We could

start the next day as the last, living it over, perfecting it.

It was as easy as unlacing our fingers from one another.

While Odysseus was off on one of those promises, we were sure

the bed had grown enough to lift off the roof.

Inside became outside. Animals wandered in following moths following light.

3.

We thought of lion summertime, speckled deer, antsy rabbits,

baboons, green parrots and crows sidestepping her bed’s branches,

invisible to the suitors, who only saw Penelope.

But the crows weren’t there for love, just olives, which they took

in the mornings like they do on our street, when the fruit fell purple and fat.

Stepping on split olives on bedcovers, they made crowsfeet all over.

This is the story you told me in the attic of our garage.

I could feel the spotted fur of the leopard, the feathered necks

of flamingoes. We were all of those animals at once,

until you were bored waiting for love.

You flew down the attic’s drop ladder, leaving me

in the rafters. You begin to sing.

previously published in Poet Lore